Moonstruck in Vietnam

November 8, 2019

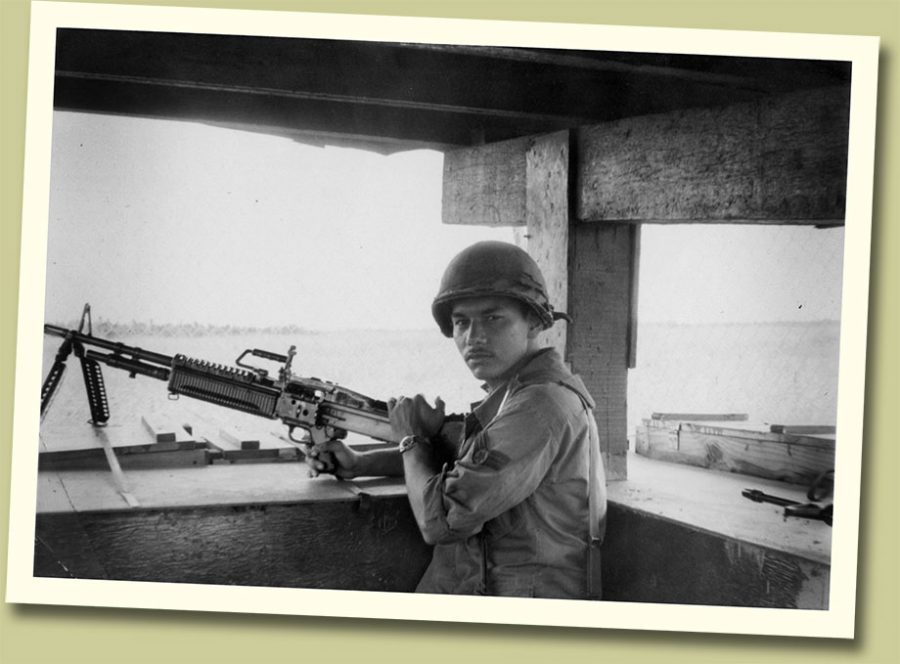

In honor of Veteran’s Day, Isabella Ramos, a sophomore, shared an essay written by her grandfather, Hector Ramos, a US Air Force veteran from the Vietnam War. Ramos served in Binh Thuy. Thank you, Mr. Ramos, for serving our country. The Prowler is honored to publish your writing.

The year 1969 for me was a time of growth, wonderment, hope, and fear. On July 20 Apollo 11 landed on the moon and a man stepped on another planetary body for the first time. Fifty years ago I was twenty-one and in the third year of my USAF enlistment. Stationed at a small airbase, Binh Thuy, I had grown to adulthood through my travels and experiences in the military. After my baptism under fire and a steady diet of mortar attacks by an unseen enemy, I hoped and prayed that if I survived I would pursue a degree in engineering.

Vietnam was never declared a war, but don’t tell that to any Nam vet or the families of the 58,000-plus KIAs and the countless others wounded. The Age of Aquarius had become a distant song. The reality of war, social unrest, protest, political conniving, and government incompetence embedded itself in our hearts and minds. But this is not about that; I am merely painting the view we had from the Mekong Delta while trying to live up to the ideals of military service and fighting for a democracy. Humankind was about to realize President Kennedy’s vision: “This nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.”

At times I feared I would fly out of there not in a Freedom Bird, but in a flag-draped coffin. I dealt with this morbid possibility of my demise with an equal sense of survival and humor. I embraced a countdown of the days left in country on my short-timer’s calendar.

On July 20, 1969, when I was six months into my tour with six to go—not officially a short timer yet, but not a cherry either—Apollo 11’s three crewmembers were preparing to land on the moon. The snippets of reports on Armed Forces Radio and Stars and Stripes were all we had, since TVs were rare and we slept during the day when most programming was available. For me and my fellow Security Policemen, it would be a typical day of sleeping from 8 a.m. until maybe 3 p.m. after another long night providing security for the base perimeter, then getting up and repeating the nightly Devil Flight routine all over again.

My assignment was 15 Alpha, a 25-foot steel tower on the far end of the base runway. As I climbed up, then went in and turned to face the tiny village and the Bassac River beyond the perimeter, before me was a bright, almost-full moon in all its glory. I sat down and immediately knew that this night would be different from any other.

Apart from the fact that history was unfolding, it could have been just another night of vigilance and fear, another nocturnal passage in this exotic, beautiful, but war-torn country. While most Americans were tuned to their TVs, I settled into my post, checked and arranged my equipment, then dug into my gear for my transistor radio. I inserted the earpiece and tuned into Armed Forces Radio for the live broadcast of the lunar mission.

Although it would be hours before the descent to Tranquility Base, I was transfixed by the moon before me and probably put myself and fellow airmen at risk. As the lunar lander emerged from that last orbit around the dark side of the moon and resumed communications, the excitement, fear of failure, and hope of success practically had me riding with them as my imagination soared.

Then, as the descent began, I vividly remember intense color as the retro rockets slowed the descent and they radioed back that they saw moon dust stirring up just before the crew counted down the last few feet to touchdown and engine shutoff. The words, “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed,” came through the earpiece. I let out a loud “Whooowie!” America was first on the moon, and I watched—yes, watched—from halfway around the world, and there was glory, victory, and renewed hope for the genius and resourcefulness of humanity.

Just then someone called out. It was my sector K9 team. He had heard my whooping. I recounted all that had just happened and the dog handler, too, was thrilled. But I was living it and soon was right back on the moon. Luckily, Victor Charlie did not spoil this night.

At about 3 a.m. July 21 on my side of the world (3 p.m. the day before on the East Coast), the decision was made to open the hatch and climb down from the lander, which would take about six hours. I would be off duty in three and the radio battery was about dead, so the first words by Neil Armstrong after stepping off the ladder were heard by a group of us in our hooch: “That’s one small step for a man; one giant leap for mankind.”

We were all in awe but tired and needed to rest. After that, we slept and maybe dreamt of home, family, girlfriends, and the possibilities of the future—a future that 58,228 would never realize. So yes, I remember the triumph of July 20, 1969, and for me it’s inexorably linked with the tragedy of the Vietnam War.

Years later I saw the video of Apollo 11 sitting on the moon and the astronauts’ walk. But the video couldn’t compare to what I, while sitting in that tower with the moon aglow in a clear black sky, saw in my mind with such clarity and wonderment. As I have relived it over and over through five decades, I wouldn’t trade it, not for anything.

Hector Ramos is a VVA life member of Grandstrand (South Carolina) Chapter 925.